On the afternoon of Election Day, Elon Musk stopped by his polling place in South Texas, then headed to one of his private planes, bound for what he hoped would be a victory party for Donald Trump at the Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida. On the way, Musk held an impromptu political rally. He posted the link to a livestream on his social network, X. “There’s only a few hours left,” Musk said, as the engine hummed and 100,000 or so people listened in. “So just make sure everyone is hounding friends and family to vote, vote, vote.”

Prior to this year, Musk ran six companies: Tesla (electric cars), SpaceX (rockets), Neuralink (brain implants), Boring Co. (tunnels), xAI (artificial intelligence chatbots) and X (Twitter). But in May, he added a seventh operation—America PAC, a political action committee that somehow managed to spend more than $170 million between then and the election.

Even more surprising was the way Musk threw himself personally into the effort. He temporarily relocated to Pennsylvania, where he traveled the state, held marathon Q&A sessions in suburban auditoriums and transformed his personal X presence into a right-wing rapid-response operation. Lots of the jokes he circulated were sexist or racist—or sexist and racist. A huge number of his posts in the final days of the campaign expressed outrage over the euthanization of a porn performer’s pet squirrel.

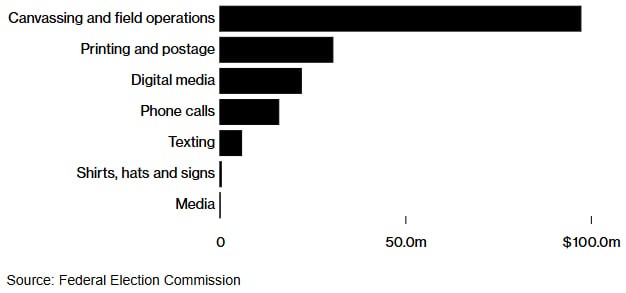

Musk’s Spending

America PAC expenditures to influence 2024 elections by type

Musk’s signature blend of transgressive humor and brazen behavior paid off, perhaps because, in Trump, he’d found a candidate who matched those traits perfectly. On Election Day the twice-impeached, 34-times-convicted felon ex-president turned out his usual base of older, White voters—and added a new cohort that was younger, more diverse and largely male. The type of guy who likes Elon Musk, in other words. “What he did is lower the barrier to being a Trump supporter,” says Josiah Gaiter, a vice president at political marketing agency Harris Media. Among younger men, “now it’s OK to like Trump.”

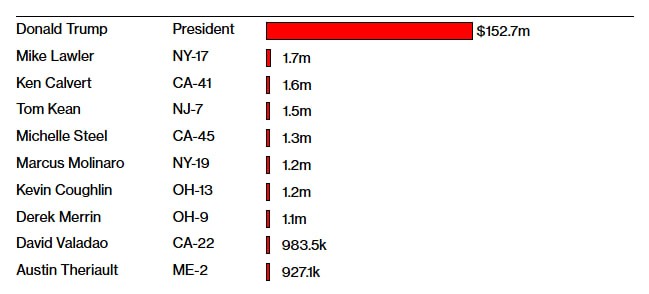

Musk’s Candidates

America PAC spending during the 2024 campaign by race

"The Dems have, I don’t know, almost every celebrity,” Musk said on the livestream. “They’ve got massive bias in the legacy mainstream news.” He told listeners that Democratic politicians were deliberately importing “illegals” to “swamp the vote in the swing states so you really don’t have a real election anymore.” This was, like so much of what Musk has said the past two years, misleading at best. The immigrants he demeaned as part of his conspiracy theory aren’t “illegals” but mostly asylum-seekers who are in the US legally, pay taxes and, of course, can’t vote.

Musk is obviously no underdog. His alliance with Trump is, if anything, a shared overdog story—maybe the greatest ever told—starring a domineering billionaire with demagogic tendencies and an equally domineering billionaire who just so happens to be the wealthiest man in the world. It’s also a story about money. We don’t know the full extent of Musk’s financial contributions to Trump’s election effort, but they at least exceed $132 million, and will probably reach $200 million when they’re all accounted for. How much might that pay off over the next four years? In the first three days after the election, the value of Tesla Inc. went up 25%, based on the expectation that proximity to a hypertransactional president will translate into amazing profits. The gain helped push Musk’s personal net worth up by $50 billion, to more than $300 billion.

Elon Musk awards Kristine Fishell a $1 million check during a town hall in Pittsburgh.

Trump has already promised some payback: rocket contracts for a new mission to Mars and rules that will cut off competitors to Musk’s supposedly forthcoming robotaxi, as well as a role in his administration. On Tuesday, Trump announced that "The Great Elon Musk" and "American Patriot" Vivek Ramaswamy will run the “Department of Government Efficiency,” a name deriving from Musk’s affinity for the acronym DOGE, which corresponds to his favorite cryptocurrency. It will decide which government programs are cut and which stay. “He’s a special guy, he’s a supergenius,” Trump said of Musk during his victory speech. “We have to protect our supergeniuses.”

Soon there might be a more accurate term for Musk: oligarch. And it could apply not only to him but also to Jeff Bezos, Sam Altman, Sundar Pichai, Satya Nadella and some of the other corporate chieftains who adopted postelection poses that ran the gamut from simpering flattery to full-blown groveling in hopes of getting what they want from Trump. Their pet issues seem to include more favorable treatment of mergers (Nadella, Pichai), a lighter touch on AI regulations (those guys plus Altman) and avoiding retribution for news published in publications they own (Bezos).

Will their efforts work? Trump’s track record doesn’t inspire confidence, and the wave of cancellations that hit the Washington Post, which lost 10% of its subscribers within days after Bezos decided to kill his newspaper’s endorsement of Kamala Harris, hints at a possible backlash the executives—and the investors who bid up Tesla’s stock—may not fully appreciate.

In the days after the election, Trump and Musk seem to be riding the world’s most intense contact high. Musk is effectively camped out with Trump’s inner circle at Mar-a-Lago, showing up in family photos and joining Trump’s calls with world leaders. The president-elect has so far treated Musk as both a trophy and a confidant, heedless of the possible national security concerns involved in, say, putting Musk on the phone with Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskiy (even though Musk has apparently been in secret contact with Russia’s Vladimir Putin) or threatening to pull out of NATO as retribution for European attempts to regulate Musk’s companies.

Musk with members of the Trump family at Mar-a-Lago.

Musk, meanwhile, tweeted up his usual pro-Trump storm, implying he might try to fire 80% of government employees and abolish the Department of Education, amplifying posts that declare the Federal Reserve unconstitutional and proclaiming that “Daddy’s home.”

This is manic exuberance of a sort that surely can’t last—and indeed mustn’t if Trump has any hope of governing effectively.

Musk is a good talker who’s quick on his feet. He also has an instinctive understanding of the young male id, perhaps because in many ways he acts like a teenager. (He’s 53.) This can put him at odds with analysts and investors who don’t, for instance, think fart noises and the numbers 420 and 69 are comedy gold, and who can’t quite grasp that, for Musk and his fans, the tastelessness is the point.

It can also be hard for outsiders to appreciate that although X is an abject business failure, it’s a smashing political success. Musk took a modestly popular social media network and transformed it into a distribution platform for right-wing media, memers and a not-small number of actual White supremacists. This pushed away throngs of users and advertisers and sent the company’s value plummeting almost 80% since the 2022 acquisition. But X still has a large and youthful audience that’s interested in Trump, sports, video games and crypto—and that isn’t necessarily put off by the absence of Sara Bareilles, Toni Braxton and NPR. A November survey by YouGov Blue, a pollster that works on behalf of left-leaning groups, found that men age 18 to 29 get most of their news from social media and that X is the most popular outlet, ahead of YouTube and TikTok.

It was this cohort that Musk had his eye on when he began funding America PAC. The organization had three basic goals to help Trump: register new voters, encourage supporters to vote early and turn out those who might not vote. It deployed paid canvassers rather than volunteers and spent heavily on direct mail and social media ads that were attuned to his audience’s edgelord sensibilities. One 15-second spot began with a bearded young dude slouched on a couch. “If you sit this election out, Kamala and the crazies will win,” a gruff voice intoned, before describing Trump as an “American badass.” Another ad warned that Harris would ban pickup trucks, red meat and Zyn nicotine pouches. A third called Harris “a big ole C word.” (The “C” stood for “communist,” though you didn’t have to be a member of the manosphere to catch the implied slur.)

An America PAC video ad.

The PAC’s early days were chaotic. Contractors, echoing long-standing complaints lodged by employees at Tesla and SpaceX, kvetched about unpaid bills, erratic decision-making and violations of standard labor practices. And yet, Musk was remarkably productive: Political campaigns typically take years to set up, but over the course of several months, Musk and his deputies—including Chris Young and Generra Peck—hired an army of 2,000. Andrew Romeo, a former adviser to Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, ran North Carolina. David Rexrode, who’d worked for Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, oversaw Pennsylvania and Michigan. Chris Carr, Trump’s political director in 2020, took Arizona and Nevada. Most canvassing operations try to save money by sending door knockers to more densely populated areas, where they can visit as many homes as possible. But a person familiar with the PAC’s operations, who requested anonymity because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly, says Musk’s funding allowed state directors to send canvassers to more rural areas, where Trump was able to drive up his vote count. The PAC knocked on about 11 million doors, this person says.

Musk spent freely in other ways, too. When a campaign rents a contact list to send emails and texts to potential voters, it typically spends no more than $10 per lead. Musk built his own list from scratch. He offered $47 to anyone who referred a registered voter in a swing state to an America PAC petition that required them to include their email address and cellphone number. Musk later raised the offer to $100 for voters registered in Pennsylvania. Then he announced he’d give away $1 million every day to a lucky petition signer. The offer was arguably against the law, attracting a lawsuit from Philadelphia’s district attorney attempting to stop the giveaway that was denied just before Election Day, but it also generated media attention. Musk’s petition eventually got more than a million names on it. “That’s a good number,” says Harris Media’s Gaiter. “It could be deployed in school board races, state treasurer races, district attorney races.” (On his election livestream call Musk indicated this is more or less his plan. He said America PAC would “aim to weigh in heavily on the midterms.”)

Musk stumping for Trump at Madison Square Garden.

But Musk’s most important move was simply injecting his personal brand into the PAC’s efforts. On Oct. 5 he appeared onstage at a Trump rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, at the same spot where Trump had survived an assassination attempt. He didn’t just speak: He leaped into the air, wore a black MAGA hat and declared himself “dark MAGA.” (The campaign instantly adopted the coinage, which means something like “so in love with Trump it’s scary.”) Musk held a series of town halls across Pennsylvania, drawing younger audiences that followed him but didn’t necessarily know much about Trump. And then, on Oct. 27, he featured at Trump’s showcase rally at Madison Square Garden in New York, where he had higher billing than Trump’s running mate and his children.

On the day before the election, Joe Rogan, the country’s most popular podcaster, dropped an interview with Musk, as he’d done with Trump the week before. “This is a message to the men out there,” Musk said as Rogan nodded along. “Vote like your life depends on it.” Rogan, who endorsed Bernie Sanders in 2020, said he was on board with Trump and made it clear that it was Musk’s doing. “The great and powerful Elon Musk,” Rogan later wrote on X. “He makes what I think is the most compelling case for Trump you’ll hear, and I agree with him every step of the way.”

Musk wasn’t the only rich guy to see his net worth increase in the days following Trump’s victory. Among the big winners were investors in private prison companies, crypto ventures and nuclear energy producers. The thinking behind these so-called Trump trades (buying assets in anticipation of a Trump win): Private prisons will benefit if Trump rounds up and deports millions of immigrants; crypto values will rise if Trump creates his promised strategic Bitcoin reserve; and nuclear companies will benefit from Trump’s claim that he’ll build new reactors.

Some aspects of Musk’s own Trump trade follow similar logic. On the campaign trail, Trump suggested his government would fund Musk’s plan for a crewed Mars mission by 2028—a proposition that could be worth billions of dollars, if not tens of billions, to SpaceX, which already launches rockets for NASA and the Department of Defense.

An even more straightforward potential payoff involves Starlink, the satellite internet service owned by SpaceX. Musk has been loudly complaining about being left out of a $42.5 billion subsidy program passed under President Joe Biden that pays for fiber-optic broadband in rural areas. Instead of using the money to lay fiber, the government could give some of it to Musk, says Blair Levin of New Street Research, a telecom research firm. Any money that Musk doesn’t spend could be returned to the US Treasury in the name of efficiency.

Other parts of Musk’s Trump trade are so speculative they border on fanciful. The Tesla stock price run-up seems fueled by an assumption that Trump will unilaterally legalize the company’s planned robotaxi—a claim Musk made during Tesla’s last earnings call, a few weeks before the election. “If there’s a Department of Government Efficiency, I’ll try to help make that happen,” Musk said, adding that the regulations would apply to all car companies, not just Tesla. The problem is that Tesla hasn’t actually developed a working robotaxi or even shown signs of being close to one.

Moreover, while many Tesla investors fit the profile of Trump voter or Musk fanboy, the people who actually buy Musk’s electric cars tend to be middle-class centrists who care about climate change. During the last Trump presidency, Tesla customers responded to his ban on Muslim immigration by canceling their orders, even though Musk was only tangentially connected to Trump’s administration back then. It seems likely the backlash will be stronger this time.

And then there’s the interpersonal dynamic between Musk and Trump. Pretty much every influential business leader who’s gained proximity to Trump has eventually been forced out of his orbit in humiliation. The half-life of Trump influence is so brief that it has a jokey shorthand—a “Scaramucci,” referring to the 10-day period that Anthony Scaramucci, the investor and former Trump confidant, lasted as White House press secretary before being fired in 2017. “Elon Musk and others, right now they’re in the halcyon moment with Donald Trump,” Scaramucci said in a radio interview in early November. “But they will come to the Hades moment with him. It’s just a matter of time.”

Even if Musk lasts more than a few Scaramuccis, and even if his businesses can endure customer boycotts, neither Musk nor Trump is terribly popular. (An NBC News survey in late September had Musk’s popularity at 34%; as of Nov. 11, FiveThirtyEight’s running average of surveys has Trump at 44%.) And that’s before any tariffs or deportations. If Trump wanted to make good on Musk’s promise to cut more than $2 trillion from the federal budget, it would almost certainly require cuts to Social Security and some of the most popular government programs. That would attract fierce opposition, not just from Democrats but also from Republicans, whose control of Congress will be narrow even if they win the House.